创意从何而来?

01 Sep 2017

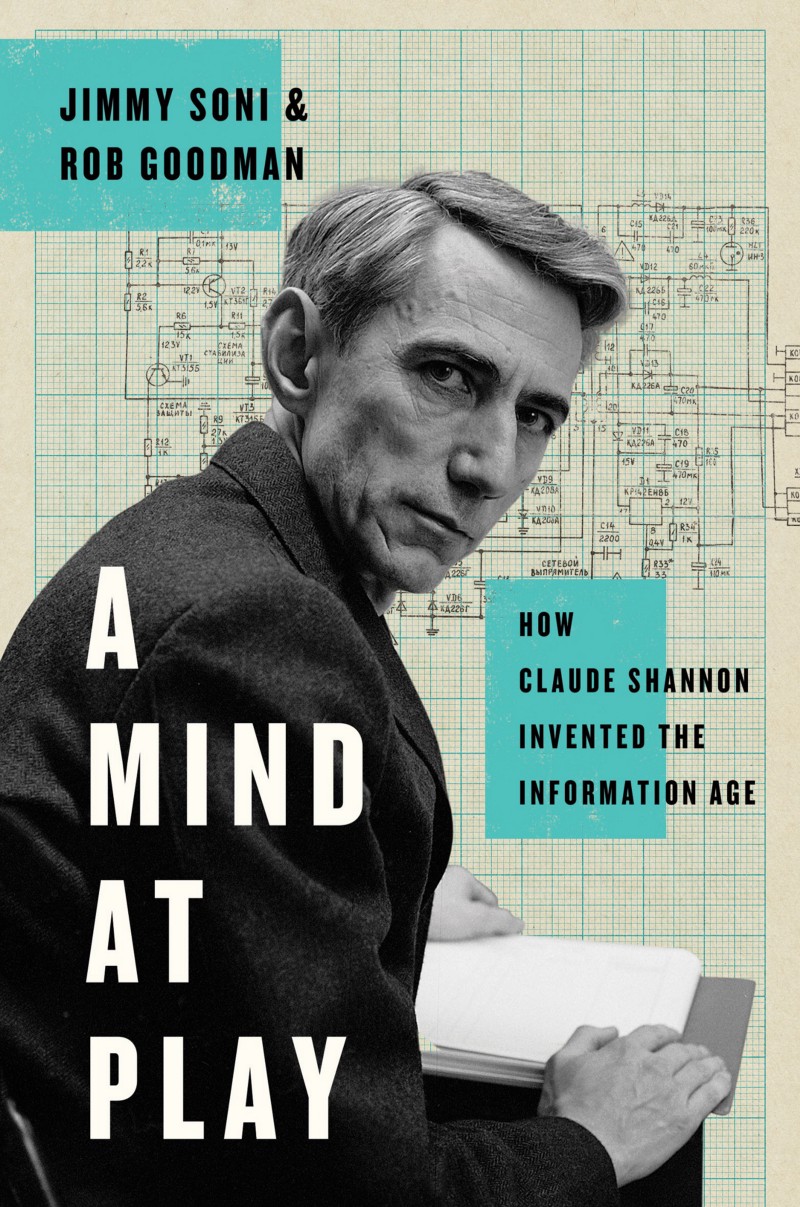

(题图来自 《香农传》(A Mind at Play))

Claude Shannon 是「信息论之父」。

21 岁时,他完成了一篇惊人的硕士论文,展示了二进制交换机如何能够执行所有的逻辑功能。Walter Isaacson 认为,这一观点是「所有数字计算机背后的基本概念」。

32 岁时,他发表了《通信的数学原理》,被称为「信息时代的大宪章」,其中的「比特」(bit)概念,展示了如何将信息量化,并演示了电子信息如何被极度压缩后在任何两个点之间准确传递。

1948 年的「信息论」是你可以看到这篇文章,以及我们相互之间发送 Email 或用 IM 进行沟通的原因。在数字时代来临之前的好几十年,Shannon 就为我们准备好了理论基础。

他是如何做到的?

在一份未曾公开发布的文档中,Shannon 试着为我们回答了「创意从何而来?」这个问题。

这是 1952 年 3 月 20 日 Shannon 给其贝尔实验室同事的一份打字稿,题名为「创意思维」(Creative Thinking)。它我们提供了一个罕见的窗口,能够窥见这位天才科学家是如何抽丝剥茧来逐步解决问题的。

创新者的特质

Shannon 首先谈到的是创新者应具有的若干特质:

- 首先,最明显的是训练和经验。不管你处于任何领域,你都应该具有该领域基本的理论素养。

- 其次,有一定量的智力和才能。你至少应达到普通人的智商,才能比较好地完成工程或研究。

以上两者,Shannon 认为,并不是充分条件。

- 他提出的第三个特质是动机。就算你拥有了所有的才能,你还是需要好奇心才能提出好问题。

- 接着,是不满足。不是那种对世界的悲观性不满,而是一种建设性不满,一切可以做的更好。

- 最后,是找到答案时的快乐,一种简单纯粹的快乐。

以上这些性格特质,都是优秀研究者所具备的。但是否有某种方法,可供所有人用于研究和探索?

Shannon 认为,是有的,并列出了 6 种方法:

1. 简化

无论你面对的是什么问题,Shannon 说,你首先要做的是简化:「你面对的几乎所有的问题都充斥着各种无关的信息;如果你能挑出主要矛盾,你就能更清楚地知道你需要做什么。」

例如,Shannon 的「信息论」,就从一个极度的简化开始:视任何信息源,从电视广播到基因,本质上是相同的。所有的信息可以被同一个单位——比特——来衡量,并且它们可以经历相同的基本过程,如编码、传输和解码。通过摆脱所有无效信息,Shannon 找到了信息的本质。

不管是什么问题,Shannon 说,「将其缩小」。他承认,在这个过程中可能会让问题「消失」。但这正是关键,「你可能把问题简化得和当初不太一样;但大多时候你能够解决这个简单问题,你可以将此解决方案不断改善,直到你回到了当初的那个问题。」

早在1977年,苹果就采用了一句格言:「简单是终极的复杂」,相信 Shannon 也会赞同。Steve Jobs 同样也理解这种简单并非碰运气。他说,「把事情简化需要付出很多的努力,要真正理解所面对的挑战并给出优雅的解决方案。」

Shannon 和 Jobs 都使「简单」化作了他们的武器,而其各自产品对当世的影响力则显示出,这是一个值得追求的目标。

2. 迁移

基于简化后的工作,你可能会尝试另一个方法:将你的问题与相似问题的已知解决方案一同考虑,并推断出答案有什么共同之处。Shannon 将其形象化地描述为「P 和 S」,「你现在有一个问题 P,在某处会有一个你还不知道的解答 S。如果你在某个你深耕的领域有相当的经验,你也许知道很多相似的问题,让我们称它为 P’,而它已经有了解答 S’,你所需要做的只是寻找从 P’ 到 P,以及从 S’ 到 S 的相似之处,从而得到原始问题的解答。」

Shannon 认为如果你是一个真的专家,「你的心智矩阵将充满 P 和 S,」许多问题已有众多解决方案。

我们能从相邻领域里找到隐藏的当前领域问题的答案,这似乎很容易理解,但多少人实际上会花时间在其他领域探索呢?作为一个新手,被空投到一个未知的智力领域是不太舒服的。但这种练习,正如 Shannon 所展现的,可以帮助每个人破解创新的障碍。

在每个阶段,他都曾发现事先无关领域之间的联系。在他的博士论文中,他将代数应用于遗传学,尽管之前并没有生物学和遗传学的背景,他还是在一年内做出了可出版的成果,他在符号逻辑和电气工程方面的多年工作为他提供了丰富的可迁移概念,让他对新的领域产生更深的理解。

Shannon 的例子启发我们,要收集和存储可能与我们的工作没有直接关系的信息和见解,可以通过类比提供有用的解决方案。

3. 多视角

接下来,Shannon 指出了多角度审视问题的价值。「改变话语,改变观点。……从某些心智障碍中挣脱出来,这些障碍让你以特定的方式看待问题。」换个角度,你可能会找到答案。

Shannon 的信息论其实是对一个老问题的重新审视——即远距离通信的问题。近一个世纪以来,人们普遍认为,解决此问题的方法,本质上是需要大声说话,即用更大的能量发送信号;而 Shannon 则证明,最可靠的方法是说得更聪明,用数字编码信息以使其不受干扰。工程学教授 James Massey 称这种洞见「似哥白尼」:换句话说,它颠覆了一种我们看待这个世界的古老方式。

把问题翻转的价值就是要避免「思维阻滞」,即被你或你所在领域已有的投入所困。就像 Shannon 所说的,「某个问题的新人」有时会是解决问题的人,他们不受已投入时间的偏见所束缚。你有一些心智障碍,而别人可以从全新的视角来看待这个问题。

这真的很难,但却很重要。

Michael Lewis,畅销书《点球成金》的作者,曾描述过一种他在编辑一部近乎完成作品的过程,从手机、打印的纸张和电脑屏幕等各个载体上反复观看,每次他都能发现不同的问题。这正是 Shannon 的建议,用以前未曾有过的方式来看待他的书面作品的「问题」。

我们自己如何能做到这一点?一种可行的方法是——广泛阅读。Shannon 的「P 和 S」策略之所以能奏效,是因为他有非常丰富的「心智矩阵」。在吸收知识方面他兴趣广泛,不仅阅读读数学和工程方面的论文,也吸纳诗歌、哲学,甚至音乐。这与 Charlie Munger 所推荐的「多学科视角」如出一辙。

4. 泛化

另一个能帮助研究工作的思维技巧,Shannon 认为,是泛化思想。事实证明,在最小级别成立的逻辑在更大级别往往也是成立的。

这在数学领域非常有用。正如 Shannon 所说,「典型的数学理论是从证明非常孤立、独特的结果、特殊的理论发展而来的。但总有人会来泛化它。」比如把它从 2 维变成 N 维;或是从某种代数演化为通用代数;或是从实数领域变为代数领域。

一旦你找到了解决方案,就花点时间来看看它能延伸到多远。

在互联网领域,Amazon 是将泛化应用得最成功的企业。从最初的卖书,到现在几乎卖所有的商品,而且从电商延伸到云计算,从线上延伸到实体店,「The Everything Store」是一种极致的泛化。

所以,如果有人在某件事上有了巧妙的解决方案,你应该马上问问自己,「我是否能将同样的原则应用到更多领域?我是否能将这个好主意用来解决更大的问题?是否还有别的地方还可以用这种特别的方法?」

5. 分解

Shannon 认为,改变观点的一种最为有力的方法就是通过「结构分析」——即将复杂的问题分解成小块。

数学家尤其如此。「数学上的许多证明实际上是通过极其迂回的过程找到的,」Shannon 指出。「当一个人开始证明某定理时,他发现他在整个地图上漫游,在证明了许多结果后,似乎并没有指向何处,然而最终会得到问题的答案。」通常,当你完成证明后,也许很容易来简化,即当你达到某一阶段后,你也许会发现过程中往往会有捷径。

当然,这种洞察力并不只限于数学。正如 Shannon 所指出的那样,他的机器和设计工作受益于同样的方法。伟大的工程师将这些挑战视为一系列小巧的步骤。不要着眼于整个问题,要找出其组成部分,并逐个解决。「但当你真正掌握并抓住了问题的本质后,你可以开始裁剪组件,发现一些部件其实是多余的,当初你并不需要它们。」

Shannon 这种方式的价值在于其允许一种巧妙的渐进主义。

正如 Shannon 所说,「对于任何心理思维,做出两个小跳跃总比一个大跳跃容易得多。」拒绝「一个大跳跃」是 Shannon 早年多产岁月的成功秘诀,《通信的数学原理》的出版是其标志。

6. 逆向

不能通过结构分析解决的问题仍可能被「逆向」解决。如果你不能用你的假设来证明你的结论,那么试想结论已经成立,反过来证明这个假设,看看会发生什么。

也许从这个方向证明相对容易,你会发现相对直接的路径。好比你在证明的路上做了个标记,然后反过来看你将如何抵达,也许只需要经历几个不那么困难的步骤。

这种「逆向归纳」有着广泛的应用,从博弈论到医学等等。在一次 TED 演讲中,国际象棋大师 Maurice Ashley 解释道,他经常用这种方法从他所想到的游戏终局来逆向推理。「当你被将死时,我在 10 步之前已经知道了结果,因为我知道你的对策」。

这种「逆向」解决问题的风格即使写作这样的领域也同样有用。虽然对于谁好谁坏,或谁对谁错,这个领域没有相对清晰的标准。但很多作者事实上喜欢从结论开始写,最后写到序言。在我自己参与编写的三本书中,打磨序言是我们向出版社发送稿件之前所做的最后几件事之一。

既然我们知道读者要去哪里,那么我们可以让他们更好地抵达那里。

以上,就是 Claude Shannon 对「创意从何而来?」的解答,看过之后我非常期待这本《A Mind at Play: How Claude Shannon Invented the Information Age》,希望能更多了解这位天才科学家的传奇一生。

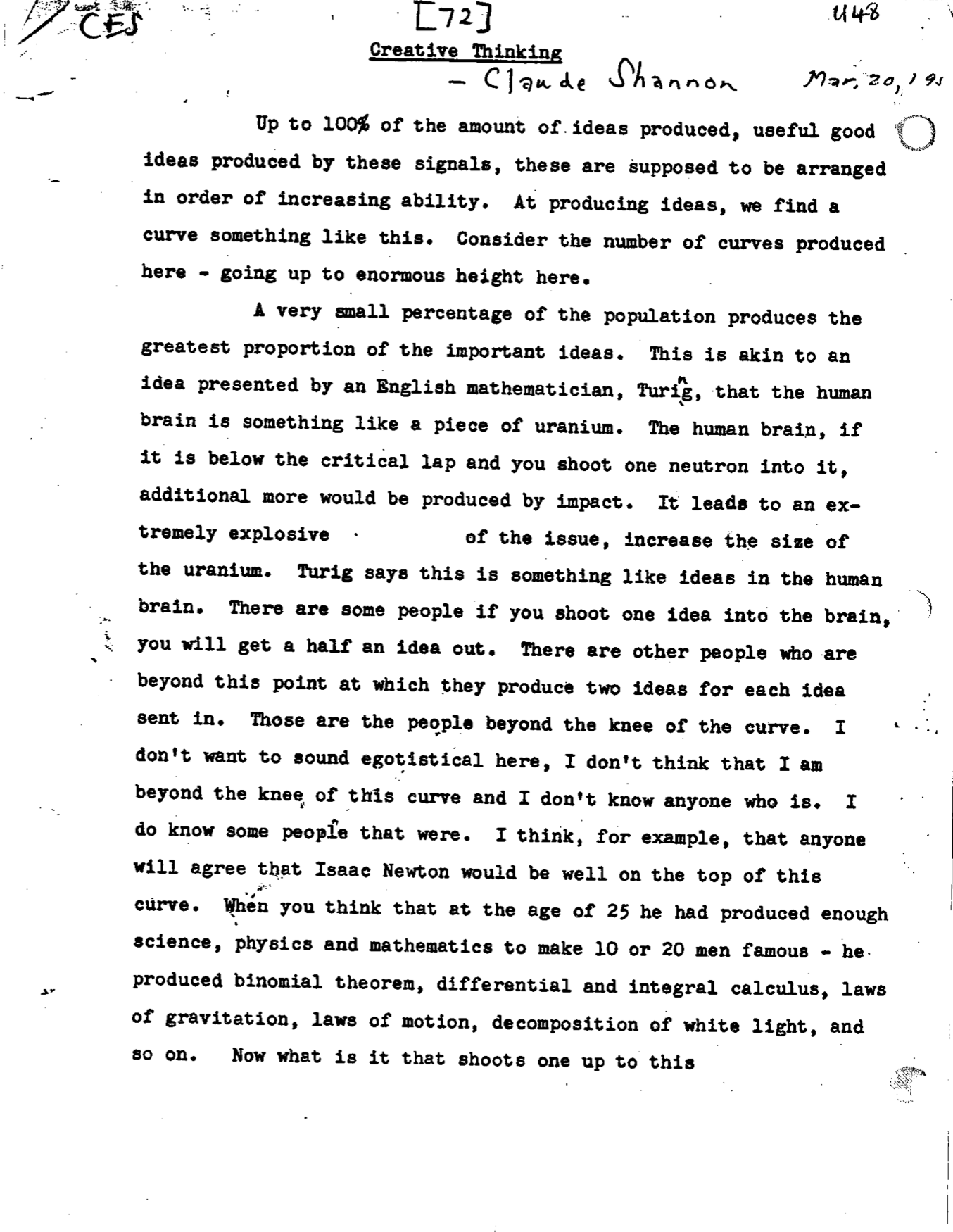

附 Claude Shannon《Creative Thinking》原文:

“Creative Thinking”

Claude Shannon

March 20, 1952

Up to 100% of the amount of ideas produced, useful good ideas produced by these signals, these are supposed to be arranged in order of increasing ability. At producing ideas, we find a curve something like this. Consider the number of curves produced here — going up to enormous height here.

A very small percentage of the population produces the greatest proportion of the important ideas. This is akin to an idea presented by an English mathematician, Turing, that the human brain is something like a piece of uranium. The human brain, if it is below the critical lap and you shoot one neutron into it, additional more would be produced by impact. It leads to an extremely explosive of the issue, increase the size of the uranium. Turing says this is something like ideas in the human brain. There are some people if you shoot one idea into the brain, you will get a half an idea out. There are other people who are beyond this point at which they produce two ideas for each idea sent in. Those are the people beyond the knee of the curve. I don’t want to sound egotistical here, I don’t think that I am beyond the knee of this curve and I don’t know anyone who is. I do know some people that were. I think, for example, that anyone will agree that Isaac Newton would be well on the top of this curve. When you think that at the age of 25 he had produced enough science, physics and mathematics to make 10 or 20 men famous — he produced binomial theorem, differential and integral calculus, laws of gravitation, laws of motion, decomposition of white light, and so on. Now what is it that shoots one up to this part of the curve? What are the basic requirements? I think we could set down three things that are fairly necessary for scientific research or for any sort of inventing or mathematics or physics or anything along that line. I don’t think a person can get along without any one of these three.

The first one is obvious — training and experience. You don’t expect a lawyer, however bright he may be, to give you a new theory of physics these days or mathematics or engineering.

The second thing is a certain amount of intelligence or talent. In other words, you have to have an IQ that is fairly high to do good research work. I don’t think that there is any good engineer or scientist that can get along on an IQ of 100, which is the average for human beings. In other words, he has to have an IQ higher than that. Everyone in this room is considerably above that. This, we might say, is a matter of environment; intelligence is a matter of heredity.

Those two I don’t think are sufficient. I think there is a third constituent here, a third component which is the one that makes an Einstein or an Isaac Newton. For want of a better word, we will call it motivation. In other words, you have to have some kind of a drive, some kind of a desire to find out the answer, a desire to find out what makes things tick. If you don’t have that, you may have all the training and intelligence in the world, you don’t have questions and you won’t just find answers. This is a hard thing to put your finger on. It is a matter of temperament probably; that is, a matter of probably early training, early childhood experiences, whether you will motivate in the direction of scientific research. I think that at a superficial level, it is blended use of several things. This is not any attempt at a deep analysis at all, but my feeling is that a good scientist has a great deal of what we can call curiosity. I won’t go any deeper into it than that. He wants to know the answers. He’s just curious how things tick and he wants to know the answers to questions; and if he sees thinks, he wants to raise questions and he wants to know the answers to those.

Then there’s the idea of dissatisfaction. By this I don’t mean a pessimistic dissatisfaction of the world — we don’t like the way things are — I mean a constructive dissatisfaction. The idea could be expressed in the words, This is OK, but I think things could be done better. I think there is a neater way to do this. I think things could be improved a little. In other words, there is continually a slight irritation when things don’t look quite right; and I think that dissatisfaction in present days is a key driving force in good scientists.

And another thing I’d put down here is the pleasure in seeing net results or methods of arriving at results needed, designs of engineers, equipment, and so on. I get a big bang myself out of providing a theorem. If I’ve been trying to prove a mathematical theorem for a week or so and I finally find the solution, I get a big bang out of it. And I get a big kick out of seeing a clever way of doing some engineering problem, a clever design for a circuit which uses a very small amount of equipment and gets apparently a great deal of result out of it. I think so far as motivation is concerned, it is maybe a little like Fats Waller said about swing music — “either you got it or you ain’t.’’ if you ain’t got it, you probably shouldn’t be doing research work if you don’t want to know that kind of answer. Although people without this kind of motivation might be very successful in other fields, the research man should probably have an extremely strong drive to want to find out the answers, so strong a drive that he doesn’t care whether it is 5 o’clock — he is willing to work all night to find out the answers and all weekend if necessary. Well now, this is all well and good, but supposing a person has these three properties to a sufficient extent to be useful, are there any tricks, any gimmicks that he can apply to thinking that will actually aid in creative work, in getting the answers in research work, in general, in finding answers to problems? I think there are, and I think they can be catalogued to an certain extent. You can make quite a list of them and I think they would be very useful if one did that, so I am going to give a few of them which I have thought up or which people have suggested to me. And I think if one consciously applied these to various problems you had to solve, in many cases you’d find solutions quicker than you would normally or in cases where you might not find it at all. I thing that good research workers apply these things unconsciously; that is, they do these things automatically and if they were brought forth into the conscious thinking that here’s a situation where I would try this method of approach that would probably get there faster, although I can’t document this statement.

The first one that I might speak of is the idea of simplification. Suppose that you are given a problem to solve, I don’t care what kind of a problem — a machine to design, or a physical theory to develop, or a mathematical theorem to prove, or something of that kind — probably a very powerful approach to this is to attempt to eliminate everything from the problem except the essentials; that is, cut it down to size. Almost every problem that you come across is befuddled with all kinds of extraneous data of one sort or another; and if you can bring this problem down into the main issues, you can see more clearly what you’re trying to do and perhaps find a solution. Now, in so doing, you may have stripped away the problem that you’re after. You may have simplified it to a point that it doesn’t even resemble the problem that you started with; but very often if you can solve this simple problem, you can add refinements to the solution of this until you get back to the solution of the one you started with.

A very similar device is seeking similar known problems. I think I could illustrate this schematically in this way. You have a problem P here and there is a solution S which you do not know yet perhaps over here. If you have experience in the field represented, that you are working in, you may perhaps know of a somewhat similar problem, call it P’, which has already been solved and which has a solution, S’, all you need to do — all you may have to do is find the analogy from P’ here to P and the same analogy from S’ to S in order to get back to the solution of the given problem. This is the reason why experience in a field is so important that if you are experienced in a field, you will know thousands of problems that have been solved. Your mental matrix will be filled with P’s and S’s unconnected here and you can find one which is tolerably close to the P that you are trying to solve and go over to the corresponding S’ in order to go back to the S you’re after. It seems to be much easier to make two small jumps than the one big jump in any kind of mental thinking.

Another approach for a given problem is to try to restate it in just as many different forms as you can. Change the words. Change the viewpoint. Look at it from every possible angle. After you’ve done that, you can try to look at it from several angles at the same time and perhaps you can get an insight into the real basic issues of the problem, so that you can correlate the important factors and come out with the solution. It’s difficult really to do this, but it is important that you do. If you don’t, it is very easy to get into ruts of mental thinking. You start with a problem here and you go around a circle here and if you could only get over to this point, perhaps you would see your way clear; but you can’t break loose from certain mental blocks which are holding you in certain ways of looking at a problem. That is the reason why very frequently someone who is quite green to a problem will sometimes come in and look at it and find the solution like that, while you have been laboring for months over it. You’ve got set into some ruts here of mental thinking and someone else comes in and sees it from a fresh viewpoint.

Another mental gimmick for aid in research work, I think, is the idea of generalization. This is very powerful in mathematical research. The typical mathematical theory developed in the following way to prove a very isolated, special result, particular theorem — someone always will come along and start generalization it. He will leave it where it was in two dimensions before he will do it in N dimensions; or if it was in some kind of algebra, he will work in a general algebraic field; if it was in the field of real numbers, he will change it to a general algebraic field or something of that sort. This is actually quite easy to do if you only remember to do it. If the minute you’ve found an answer to something, the next thing to do is to ask yourself if you can generalize this anymore — can I make the same, make a broader statement which includes more — there, I think, in terms of engineering, the same thing should be kept in mind. As you see, if somebody comes along with a clever way of doing something, one should ask oneself “Can I apply the same principle in more general ways? Can I use this same clever idea represented here to solve a larger class of problems? Is there any place else that I can use this particular thing?”

Next one I might mention is the idea of structural analysis of a problem. Suppose you have your problem here and a solution here. You may have too big a jump to take. What you can try to do is to break down that jump into a large number of small jumps. If this were a set of mathematical axioms and this were a theorem or conclusion that you were trying to prove, it might be too much for me try to prove this thing in one fell swoop. But perhaps I can visualize a number of subsidiary theorems or propositions such that if I could prove those, in turn I would eventually arrive at this solution. In other words, I set up some path through this domain with a set of subsidiary solutions, 1, 2, 3, 4, and so on, and attempt to prove this on the basis of that and then this one the basis of these which I have proved until eventually I arrive at the path S. Many proofs in mathematics have been actually found by extremely roundabout processes. A man starts to prove this theorem and he finds that he wanders all over the map. He starts off and prove a good many results which don’t seem to be leading anywhere and then eventually ends up by the back door on the solution of the given problem; and very often when that’s done, when you’ve found your solution, it may be very easy to simplify; that is, to see at one stage that you may have short-cutted across here and you could see that you might have short-cutted across there. The same thing is true in design work. If you can design a way of doing something which is obviously clumsy and cumbersome, uses too much equipment; but after you’ve really got something you can get a grip on, something you can hang on to, you can start cutting out components and seeing some parts were really superfluous. You really didn’t need them in the first place.

Now one other thing I would like to bring out which I run across quite frequently in mathematical work is the idea of inversion of the problem. You are trying to obtain the solution S on the basis of the premises P and then you can’t do it. Well, turn the problem over supposing that S were the given proposition, the given axioms, or the given numbers in the problem and what you are trying to obtain is P. Just imagine that that were the case. Then you will find that it is relatively easy to solve the problem in that direction. You find a fairly direct route. If so, it’s often possible to invent it in small batches. In other words, you’ve got a path marked out here — there you got relays you sent this way. You can see how to invert these things in small stages and perhaps three or four only difficult steps in the proof.

Now I think the same thing can happen in design work. Sometimes I have had the experience of designing computing machines of various sorts in which I wanted to compute certain numbers out of certain given quantities. This happened to be a machine that played the game of nim and it turned out that it seemed to be quite difficult. If took quite a number of relays to do this particular calculation although it could be done. But then I got the idea that if I inverted the problem, it would have been very easy to do — if the given and required results had been interchanged; and that idea led to a way of doing it which was far simpler than the first design. The way of doing it was doing it by feedback; that is, you start with the required result and run it back until — run it through its value until it matches the given input. So the machine itself was worked backward putting range S over the numbers until it had the number that you actually had and, at that point, until it reached the number such that P shows you the correct way. Well, now the solution for this philosophy which is probably very boring to most of you. I’d like now to show you this machine which I brought along and go into one or two of the problems which were connected with the design of that because I think they illustrate some of these things I’ve been talking about.

In order to see this, you’ll have to come up around it; so, I wonder whether you will all come up around the table now.